Answering the call to arms

Alexander John Wilson, aged 24, left his home in Leeds in October 1868 and headed to Rome to join the Papal Zouaves. The Zouaves were originally founded in 1860 as a volunteer regiment accepting recruits from anywhere in the world. Its purpose was to reinforce the French garrison which had defended the Pope and Papal States since restoring Pius IX to power in 1849, after the revolution of the previous year.

By 1860 most of Italy, previously composed of separate states, had been unified as the Kingdom of Italy under King Victor Emmanuel after the intervention of Giuseppe Garibaldi. [i] Then, in 1866, the Veneto was annexed and added to the land controlled by the King, leaving the Papal States as the only area holding out. Garibaldi attacked in 1867 but his troops were successfully repulsed by the Papal army at the battle of Mentana. William Edward Joseph Vavasour of Hazelwood Castle, Yorkshire, fought for the Zouaves in that encounter and returned to England in the summer of 1868, encouraging more young men, including Alexander, to respond to the call to arms. [ii] The English contingent was very small in comparison with other nationalities [iii] – 60 attended a Christmas dinner in Rome in 1869 – so Alexander’s experience was by no means common for a young man from inner-city Leeds.

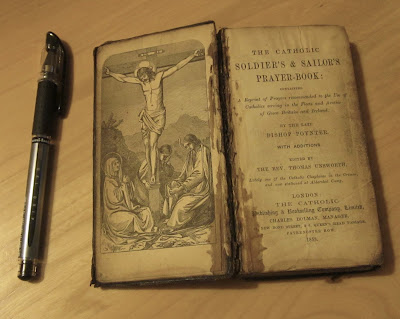

A small number of photos and documents have survived from Alexander’s time in the Zouaves, together with several other family photographs. These were in the possession of a great grandson, John Blakeley Wilson, who died in Leeds in April 2017. John appreciated that these items might be of interest, both to other members of his wider family and anyone researching the Papal Zouaves. He had intended that they should be deposited with a suitable archive but releasing them on the internet as well should make them even more accessible. The earliest photo of John’s great grandfather Alexander (referred to as AJW from this point) in the collection is one glued into his battered and stained copy of ‘The Catholic Soldier and Sailors’ Prayer Book’.

.

| ||

The original photo is now quite faint so an ‘enhanced’ version appears opposite. It shows AJW, smartly dressed, with a wing collar and watch chain. There is a dedication beneath the photo written in ink:

‘October 1868

Batley

Rev Father B Rigby’

which suggests that the book was a gift. AJW probably met Father Rigby [iv] in 1866/67 when the latter spent a year working as a curate at St Patrick’s in the middle of Leeds before moving to Batley. He was familiar with Rome, having been ordained there in around 1860 after four years at the English College, and it seems likely that, like Edward Vavasour, he influenced AJW’s decision to join the Zouaves. Perhaps the inclusion of the photo was Father Rigby’s idea, in the hope that the Prayer Book would assist identification, should the worst happen.

The Prayer Book also contains a form to be filled in by the owner along with instructions for its completion. The entry shows that AJW enlisted in Rome in 31 October 1868. The term of enlistment was two years (or six months on payment of sixty francs) and the cost of the journey to Rome was normally £6. [v] However, AJW’s travel expenses (at least from London) may have been met by an appeal fund set up by the Earl of Denbigh, a Catholic convert, spokesman for the Catholic community in the House of Lords and a leading member of the London Papal Committee. The Dundalk Democrat and People’s Journal reported on 6 March 1869 that ‘any volunteer with testimonials from a parish priest and the consent of his father and mother, who is fit for military service, will be transported free of cost from London to Rome.’

The collection of photos and documents does not include a diary or note book although it may be that such items were passed down to other family members and might still come to light. However, an idea of what AJW would have experienced can be found in Joseph Powell’s book of 1871 ‘Two Years in the Papal Zouaves’. Powell (‘JP’) enlisted in March 1868, around seven months earlier than AJW, and returned six months before him in May 1870. He was not present for the events in the summer and autumn of 1870 but includes reports in his book from other Zouaves who were still in Rome.

Life in the Papal Zouaves, 1868-1870

It took JP eight days in total to get to Rome from London by train and boat. Catching an evening train to Newhaven on Monday 9 March, he boarded a ferry to Dieppe and arrived there the following morning. A train journey to Paris followed, with a two hour delay in Rouen and the opportunity for some sight-seeing. After a night in Paris, he spent Wednesday sorting out his passport for travel to Italy and undergoing, and passing, a doctor’s examination. He left Paris by train at 3pm on Thursday afternoon with some new companions, five French recruits and a sergeant returning from leave. They travelled overnight and reached Marseilles at 7pm on Friday. There was time to tour the city before boarding a boat on Sunday morning, bound for Civita Vecchia, the port within the Papal States and in striking distance of Rome.

After nearly two days at sea, they stepped ashore at 9am on Tuesday 17 March and reached Rome station by 7pm in the evening. A sergeant met them, taking the new recruits to the barracks where JP was warmly greeted by other English and Irish volunteers. As a French regiment, all commands etc were naturally in French so extra English speakers were always welcomed by their fellow countrymen. He was given the choice of joining the Zouaves or the dragoons but decided on the former and signed up for two years. All recruits, whatever their level or standing in society, began their career in the Zouaves as privates.

JP remained in Rome for three months undergoing basic training - learning drill, how to maintain equipment and uniform and the various duties a Zouave would be expected to perform. There were several barracks dotted around the city. At first JP found himself in the Torlonia Barracks which, he explains, were conveniently situated only 6 minutes’ walk from St Peter’s – presumably at the foot of the hill by the river. Other barracks included Sora (a Palazzo in the middle of the city which also served as the Zouaves headquarters), Gesu (also in the middle of the city), San Michele (located in the Trastevere, and also a hospital), Termini (at the station) and Santa Galla (near the Palatine Hill).

Once trained, a recruit would be drafted into a company and could be sent to the furthest reaches of the Papal states to defend the borders. JP was pleased to be allowed to choose a company with several other UK volunteers and he eventually left Rome on 23 June to join them on Monte Rotondo to the south of Rome. JP describes his fellow Zouaves as ‘mostly young men, some under 20’.

As AJW arrived at the end of October 1868, he is likely to have spent the winter in barracks in Rome with the opportunity to act as a guard in Papal processions and see the sights in his free time. The opening of a club for the UK Zouaves (the ‘English Library’ at 91 Piazza della Valle) in December 1868 must have been a welcome diversion. Organised by the London Catholic Committee and the English Zouaves’ chaplain, Mgr Edmund Stonor, it provided a comfortable place for the men to relax with a library and a reading room with open fire, letter writing materials, piano, chess, draughts, cards and newspapers. A billiard room and refreshment room were also planned.

JP described various events in 1869 which AJW might have also witnessed. Carnival provided great excitement in February but also created extra work with an increase in picket duty. The Zouaves were charged with keeping order, particularly during the horse race in the Corso which closed the programme of events each day.

Lent was the time for the whole regiment to go on spiritual retreat with the different nationalities catered for in separate churches – Father Vincent [vi] of Malta took care of the UK contingent. It seems likely that this retreat led up to AJW’s confirmation at the church of St Alphonse on 18 March 1869 (as recorded in his prayer book). Lent made no difference to the Zouaves’ diet (with the exception that no meat was eaten on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday) as they had special dispensation.

Sham fights formed part of the training of all the troops based in Rome as the weather improved. JP described one such exercise (including a cavalry charge by the Dragoons) which took place on the Via Ostia (to the south west of the city beyond the Abbazia Tre Fontane) and a second on the Via Aurelia to the west.

In April there was much for the new recruits to experience. The Zouaves assembled in St Peter’s Square in stormy weather on Easter Sunday (4 April) to witness the Pope appear on the balcony of the portico of St Peter’s and give Apostolical Benediction to the crowd below which included many visitors. Easter Monday saw a review of the Papal Army at the Villa Borghese by the Commander in Chief, General Kanzler.

However, April 1869 was particularly special as Sunday 11 April was the 50th anniversary of the ordination of Pius IX and the cause of three days of celebration. JP describes how the streets were packed with carts and wagons filled with gifts of corn, wine, oil, flowers etc for the Pope. In the evening of 10 April, St Peter’s Basilica, including the dome, was illuminated in two stages; JP found the second ‘golden’ stage particularly impressive. Mass on Sunday, the anniversary itself, was attended by a huge crowd and at 4pm the Pope appeared on the balcony overlooking the Piazza to hear a choir of 1,000 soldiers from the Papal Army, including Zouaves, sing a hymn accompanied by seven military bands. The hymn was specially composed by Gounod for the occasion. JP does not comment on the quality of the performance but the correspondent of the Morning Post reported that the crowd pronounced it a complete fiasco (although he suggested that their judgement might have been affected by waiting over an hour for the band to strike up). [vii] The hymn was followed by the Apostolical Benediction on everyone present and the day ended with a firework display. On the following day the whole city was again illuminated.

St George’s Day was another important occasion for the English Zouaves. On the previous evening, Mgr Stonor entertained them to dinner at the Restaurant de Paris [viii] along with other guests including Edward Vavasour. Then on the day itself, they had an audience with the Pope, again arranged by Mgr Stonor, and were each presented with the Medal of Immaculate Conception. This was followed by a tea party at the English Library, organised by two ladies who were resident in Rome, and an ‘Ethiopean entertainment’ with songs, jokes and a farce performed, to great acclaim, by a group of Zouaves.

The festivities of April over, JP and his company left Rome on 17 May, armed with new Remington rifles, and marched through beautiful countryside to Montefiascone, near the northern frontier of the Papal states, about 60 miles north of Rome. They were billeted in part of a Franciscan monastery and, with duties which were not too onerous and no sign of imminent attack, it sounds a pleasant place in which to spend the summer. A man might expect to mount guard once every twelve days and take part in exercises three times a week - on those days the routine was reveille at 4am, roll call at 4.45 followed by skirmishing drill until 7.45. They bathed in Lake Bolsena three times a week and had plenty of free time although they were confined to barracks from 1pm to 4pm every day except Sunday to avoid the heat. The routine was broken up by a six-week stint in the village of Bolsena where JP and fellow Zouaves acted as gendarmes.

JP returned to Rome with his company at the beginning of November 1869. The city was a hive of activity in the build up to the Vatican Council, the first Ecumenical Council to be held in the Vatican itself. This was a huge event, opening on 8 December 1869 and attracting royalty and the aristocracy as well as clergy.

The Earl of Denbigh, a great supporter of the English Zouaves, arrived in December and was one of the guests at their Christmas dinner in the Café Nuovo on 26 December. Seventy-three sat down to dine, including sixty Zouaves and Mgr Stonor, their Chaplain. According to Baedeker [ix], the Café was in the Palazzo Ruspoli near the junction of the Corso and the Via di Fontanella. JP reports that, after dinner, everyone repaired to the nearby Mausoleum of Augustus to be photographed but the group photo was a failure as some members of the party could not keep still. However, at least one successful photo was taken during the Earl of Denbigh’s visit and is part of the Wilson collection. It features eleven Zouaves grouped around the Earl of Denbigh and Mgr Stonor. Perhaps it was taken during the trip to the Mausoleum of Augustus although the setting looks like a studio. It may have been decided that there was a better prospect of a picture to send to the folks back home if smaller groups were photographed indoors. Close examination of the surround revealed ‘Photografia Didoli, Roma’ pressed into the cardboard.

AJW is the tall figure in the centre of the photo at the back (without a cap), his face looking a little thinner than in the photo in the Prayer Book. The Zouaves are wearing their distinctive uniform in grey with a red trim, and kepis.

Unfortunately someone, perhaps one of AJW's children or grandchildren, decided to 'enhance' the photo by inking in the eyes and moustaches of several of the Zouaves (and adding one or two blots in the process). It probably seemed a good idea at the time.

Unfortunately someone, perhaps one of AJW's children or grandchildren, decided to 'enhance' the photo by inking in the eyes and moustaches of several of the Zouaves (and adding one or two blots in the process). It probably seemed a good idea at the time.

However, the Wilson collection also contains a newspaper cutting from ‘the Universe’ of 1 March 1929 which features another copy of the photograph without the artistic additions. This cutting was sent to the paper by the son-in-law of Benjamin Thomas Holtham [x], the Zouave sitting on the floor on the right-hand side. Benjamin also survived the campaign, married and had a family, and died in Cardiff in 1917.

There is another photograph of AJW which looks to have been taken at some point in 1870, later than the Christmas photo. His face looks thinner than in the earlier picture – possibly because he has a full beard, but he may also have contracted malaria when in Italy. He is described in the 1901 census as ‘invalid through ague’. He is wearing his full dress Zouave uniform including astrakhan talpack with plume, tassel and regimental badge. The badge is of a design introduced in 1869 representing a sunburst with Papal insignia in the centre. On each cuff, he has acquired a broad stripe which looks to be the same colour as the original narrow stripe and indicates promotion to corporal. Perhaps this prompted a desire to send a photo to his family. There is nothing on this photo, or the reverse, to show when or where it was taken.

For a time, life for the Papal Zouaves in 1870 followed a similar pattern to that of 1869. After the excitement of Carnival in the lead up to Ash Wednesday, the British Zouaves once again went on a Lent Retreat, this time led by Father Walshe. JP’s two years in the Zouaves came to an end on 11 April as he had been persuaded to return to England by those at home. However, he didn’t leave Rome until the end of the month giving him the opportunity to attend, and later describe, many of the ceremonies over the Easter period. He enjoyed the fireworks in the Piazza del Popolo on Easter Monday and the following evening attended amateur theatricals performed by the English Zouaves at the Teatro Argentine (a great success watched by ‘a very select company of spectators, including some of the elite of English Catholic society in the city’). On 20 April he and some friends attended the horse races on the Via Appia and saw the illumination of the city. After a trip to Tivoli, he returned to Rome in time for St George’s Day when, once again, he joined the English Zouaves (58 in number) for an audience with Pius IX. JP commented that the Pope looked much sadder than usual.

JP left Rome for the UK on 28 April 1870 so his eye-witness description of events ends there.

Beginning of the end

Life continued as normal for a short while after JP’s departure. The Vatican Council laboured on and finally passed a new constitution on 18 July which enshrined the doctrine of Papal infallibility. However, the following day, Prussia declared war on France and the delicate balance of power, which had left the Papal States untouched since the Battle of Mentana, was altered. The French garrison was recalled to France and, once they had left Rome on 6–7 August leaving the volunteer troops to defend Rome, the Italian army of King Victor Emmanuel was mobilized.

When France surrendered to the Prussian army at the battle of Sedan on 2 September, it was only a matter of time before the Italians would march on the city, confident that the French would not come to its aid. Although an Italian raid was briefly repulsed on the northern border, the decision was taken to withdraw the Papal army to Rome.

A letter from Victor Emmanuel was delivered to the Pope by his ambassador San Martino on 10 September with Italian troops already camped outside the walls. It explained they intended to occupy the city but that the Pope’s independence would be respected. San Martino was sent away with a flea in his ear as the Pope still refused to believe they would dare to invade Rome.

The following days saw one or two skirmishes as the Papal troops demonstrated a willingness to stand their ground, even though the Pope had ordered his army to surrender if the walls were breached at the Porta Pia.

The Italian bombardment began in earnest at 5am on 20 September. Papal troops attempted to defend their positions but the odds were hopeless and around 10am the wall at Porta Pia was breached. 10 Zouaves died in the defence of the city and 37 were injured. [xi]

One of JP’s fellow English Zouaves was stationed at the Lateran Gate near Santa Croce on the south east side of the city. His description of events on 20 September is included in Chapter 29 of JP’s book and the following details are taken from that Chapter.

Bugles sounded the ‘Cessez le Feu’ as white flags were flown from the walls, to the dismay of many of the young men who had responded to the call to arms. Before long, one of their officers arrived to confirm that the Papal army had surrendered and they must lay down their arms. At around 2pm the order came to march to St Peter’s Square. This would have taken them through the heart of the city past the Forum and Coliseum and many sights which had become so familiar to them. The crowds of Roman citizens in the streets were ‘anxious-faced, well-conducted and respectful in their demeanour towards us’.

The defeated troops spent the night in the Piazza and the following morning received their pay and a message from the Pope thanking them for their service. The writer and some fellow Zouaves passed the time in a café where Lieutenant Colonel de Charette asked to join them, telling them he had always been pleased with his brave English Zouaves. About midday, bugles sounded the call to arms. Once the men were drawn up in columns and ready to march, Pius IX appeared at a window of the Vatican and, after a last Papal benediction, the troops left the city, marching through the Porta Angelica on the north wall of the Vatican. Turning left, they followed the Vatican walls until they reached the road running south (see sketch map of Rome above).

At the Porta San Pancrazio on the west side of the city, they were met by a contingent of Italian troops drawn up to salute them, bands playing and accompanied by three Generals on horseback and three Zouave generals on foot. The Zouaves saluted their commanders and marched past with bugles sounding and bayonets fixed, before throwing down their weapons in a field near the Pamphili Gardens. Carrying their packs and great coats, they set off in the heat of the day for the station at Ponte Galeria some 10 miles away. On reaching the station, they were drawn up by regiment to await trains bound for Civita Vecchia.

It was evening before the English Zouaves were crammed into railway carriages, fourteen men or more packed into a compartment. Arriving at the port late in the evening, the men were grouped by their country of origin and housed overnight in temporary accommodation – an empty prison building in the case of the English contingent. At 8pm the following day they were marched down to the harbour and 750 men of various nationalities were packed onto barges which took them out to the screw steamer Liguria.

The packed ship sailed at 10pm and arrived in Genoa at dusk the following day, too late to disembark. After another uncomfortable night on board, they reached land at daybreak where they were supplied with a mess tin, spoon and small blanket before a five mile march to Fort Monteratti on the summit of a mountain to the north of the town. The troops were relieved that officers allowed them to buy food and wine in shops en route. Many shopkeepers looked on them kindly and refused payment.

A familiar face appeared as they marched through the town. Mgr Stonor had followed his charges on their journey and would be active in ensuring they were supplied with essentials during their stay in Genoa and in finding a ship to take them home. After another uncomfortable night, sleeping on straw, they marched back to the town and into the San Benigno barracks which was to be their accommodation until 1 October. Here they were free to go where they liked, they received the same pay as the local Italian soldiers and were allowed free use of two good canteens.

On 1 October the British and Irish Zouaves and the contingent from Canada finally embarked on board the India, a vessel chartered by Mgr Stonor to take them to Liverpool. The Leeds Mercury of 15 October describes how the India arrived in the Mersey around noon on Friday 14 October with large crowds gathering to welcome the men home. Once the quarantine flag was lowered (there had been one death from consumption during the voyage), several supporters, including the Earl of Denbigh, were ferried out to meet them. The UK troops disembarked during the afternoon but the Canadians remained on board for the night whilst arrangements for their accommodation were made in the town. The Zouaves were described as ‘remarkably fine young fellows, tall and wiry……. with any amount of “fight” in them’. Their uniform was ‘exceedingly picturesque and neat’ and they ‘the Irish, English and French-Canadian detachment…..from their conversation are all well-educated and evidently of good standing in society’. They were accompanied by two chaplains, one French and the other English (presumably Mgr Stonor). Some made allegations of brutal murders by ‘the marauders who entered Rome with the Italian troops’ although it is not clear whether such events were witnessed or rumoured.

It may be that British troops such as AJW stayed in Liverpool overnight before saying goodbye to their comrades. However, it can’t have been long before they boarded trains, dressed in their striking uniform, and headed for home.

AJW’s family background and what happened next

The 1871 census shows AJW, his adventure over, back at 27 Beckett Street in Leeds, with his parents Alexander John Snr and Jane Walker Wilson and three of his siblings - James Joss, Jane Taylor and Charles John. The family had travelled many miles before eventually landing in Leeds in the mid-1860s. AJW was born in Inverurie, north west of Aberdeen, and his father, Alexander John Wilson Snr, came from even further afield – Halifax, Nova Scotia. He was born there on 8 June 1812 to parents James Wilson, a master dock builder, and his wife Margaret Harper. [xii]

AJW Snr (pictured below) first appears in UK records in the 1841 census when he was a single man working as a policeman in Aberdeen. It is possible that he had only just moved to the UK – an ‘Alexander Wilson’ was in the Nova Scotia military in 1839/40 and had a signature resembling that of AJW Snr above although that may just be coincidence.

He married Jane Walker Taylor (below), the daughter of an Aberdeen grocer and spirit dealer, on 11 October 1843 and the couple set up home in Inverurie where he had taken a post in the rural constabulary. They were still in Inverurie on 19 August 1844 for the birth of their first child, the future Zouave AJW Jnr, but then appear to have moved back to Aberdeen where two daughters, Marjorie Taylor and Jane Walker, were born in the Old Machar area in 1846 and 1849 respectively.

AJW Snr (pictured below) first appears in UK records in the 1841 census when he was a single man working as a policeman in Aberdeen. It is possible that he had only just moved to the UK – an ‘Alexander Wilson’ was in the Nova Scotia military in 1839/40 and had a signature resembling that of AJW Snr above although that may just be coincidence.

He married Jane Walker Taylor (below), the daughter of an Aberdeen grocer and spirit dealer, on 11 October 1843 and the couple set up home in Inverurie where he had taken a post in the rural constabulary. They were still in Inverurie on 19 August 1844 for the birth of their first child, the future Zouave AJW Jnr, but then appear to have moved back to Aberdeen where two daughters, Marjorie Taylor and Jane Walker, were born in the Old Machar area in 1846 and 1849 respectively.

When John Taylor arrived in 1850, they were living further south in Dysart, Fifeshire. AJW Snr was still in the police and described as a ‘police officer and sheriff officer’ in the Dysart census for 1851. However, by the time their next son James Joss was born on 15 August 1854, AJW Snr had taken an indoor job as a ‘writing clerk’ and moved the family to Berwick upon Tweed. As his future career was in the railways, it seems likely that his new employer was a railway company and it was this opportunity which had encouraged him to move his family once again. They lived on the north side of Berwick in the Greenses, only five minutes’ walk from the station.

By 1858 they had moved once more, this time to Carlisle where Charles Joseph was born. They were living north of the river in the Stanwix area when the 1861 census was taken, a couple of months after the birth of another daughter Mary Bristol. AJW Snr was described as a railway clerk in that census but by the time their youngest child, Margaret Harper, arrived in Carlisle on 2 July 1864, he had been promoted to the position of Inspector in the Railway Clearing House and they were living in West Walls which was much nearer the station.

In the meantime, AJW Jnr had headed further south to Yorkshire as records show that he enlisted in the West Riding police on 15 August 1864 (just before his 20th birthday, although he gave his age as 21). and that he joined the Dewsbury force on 7 September. He is described as 6 feet tall with light brown hair, grey eyes and fair complexion with scars by the side of his left eye, over his left ear and on his forehead.

However, the records also indicate that this was not his first job in the area - his previous employer is given as the Railway Clearing House in Wakefield, presumably a position arranged by his father. It looks as though AJW, or perhaps his employers, decided an office job was not for him, hence his move into the police. In the event, his new career did not work out in the way he might have hoped as he resigned from the force on 2 June 1865 due to ill health. No further explanation is given.

However, the records also indicate that this was not his first job in the area - his previous employer is given as the Railway Clearing House in Wakefield, presumably a position arranged by his father. It looks as though AJW, or perhaps his employers, decided an office job was not for him, hence his move into the police. In the event, his new career did not work out in the way he might have hoped as he resigned from the force on 2 June 1865 due to ill health. No further explanation is given.

He did receive one mention in the newspapers (the Leeds Mercury of 8 March 1865), during his time in the force, when he gave evidence to the Dewsbury magistrates after arresting a servant accused of stealing ladies’ and children’s underclothes from her employers. She was committed for trial at Pontefract but acquitted.

The rest of his family (except sister Marjorie who had returned north to Aberdeenshire and married Francis Harker in Newmills on 11 July 1864) followed AJW Jnr to Leeds in the mid-1860s, possibly through his father’s job with the Midland Railway. The first record of them living in Leeds is a sad one – daughter Mary died on 16 June 1866 and was buried in Killingbeck Cemetery.

The next mention of the family appears in the York Herald on 4 April 1868 in a report of Gresley v Midland Railway Company regarding an incident which occurred almost a year earlier on 24 April 1867. AJW Snr had been on board a train which left the rails at Methley Junction and crashed into a coal wagon. A passenger, Isaac Gresley, became very ill after the accident (he died shortly after the court case) and sued the Midland Railway Company who he blamed for his condition. AJW Snr (who explained he was an employee of the Midland) gave evidence that he had seen the claimant standing on the tracks after the crash, apparently unhurt, shouting that he would make the railway company pay; a local surgeon gave evidence along similar lines. Nevertheless, the jury found in favour of the Plaintiff and awarded damages of £1,500.

Another glimpse of the Wilsons occurs on 27 September 1869, nearly a year after AJW Jnr set off for Rome, when their youngest child Margaret died and was buried in Killingbeck with her sister. So the family’s first few years in Leeds must have been a sad and worrying time with the deaths of the two youngest children and the eldest son away in Rome.

There must have been huge relief in October 1870 when the tall figure of AJW Jnr appeared at the door in his Zouave uniform. With his father still working for the Railway Clearing House, it is perhaps no surprise that AJW Jnr took a job with the railways. Railway records show that he signed up on 27 February 1871, working as a policeman (wage 18/- per week) to start with. However, by the time the census was taken he had become an excess fares collector.

AJW Jnr married local music teacher Caroline Blakeley in Leeds at Mount St Mary’s in Leeds on 23 June 1878. Newspaper reports comment on her beautiful singing voice and she regularly performed in public around Yorkshire including concerts at Leeds Town Hall. The Whitby Gazette of 10 August 1872 includes the running order for an evening concert in St Hilda’s Hall, Whitby in which Caroline played a leading role. [xiii] Perhaps AJW Jnr heard her sing before he met her in person. She continued to perform for a time after her marriage – for example, on 26 February 1879 she took part in a full-dress concert at the Assembly Rooms in Thirsk for the benefit of All Saints’ Poor School. The photo below was possibly taken in 1878 to celebrate their marriage.

The couple had four children in the 1880s starting with Alexander John in 1880, then John Blakeley in 1881, Arthur Taylor in 1885 and Agnes Mary Alice in 1886.

With a young family, it may have been difficult for AJW Jnr to see much of his parents who had moved to Lancashire in the late 1870s - AJW Snr (aged 68) and wife Jane were living at 5 Park Avenue, Gorton in 1881. He is still described as a Clearing House Inspector so the move may once again have been related to his job with the Midland Railway. However, before long the couple went north to Glasgow to live with their son, James Joss and his wife Emma. Jane died there on 7 March 1886 and her husband followed, two months later, on 7 May. James Joss and family subsequently emigrated to Australia.

AJW Jnr and Caroline remained in Leeds and in 1891 were living at 16 Alfred Place with their four children, Caroline’s mother Alice and an adopted daughter, Lizzie Hollis Wilson, aged 13. By then, AJW Jnr had left the railways and was working as a rent collector. It was around this time that AJW Jnr began to develop some sort of paralysis, a symptom of a condition which eventually led to his early death.

In 1894 AJW Jnr makes an appearance in the newspapers as a result of an accident. The Leeds Times of 13 January 1894 reported from the Leeds County Court that Alexander John Wilson, debt collector of 16 Alfred Place, had sued James Henry Battey, a mineral water manufacturer trading as Thomas Clarkson, for the sum of £5. AJW gave evidence that his legs were paralysed and as a result he used a tricycle to get about, propelled with his hands. On 30 October 1893 he was travelling in this fashion along Call Lane towards Briggate when a wherry [xiv] belonging to James Henry Battey tried to overtake a bus on the opposite side of the road. The wherry collided with AJW’s tricycle throwing AJW from his seat, cutting his fingers and doing a lot of damage to the trike. AJW won his case and was awarded the damages in full. There is no indication of whether the paralysis was caused by an injury during his time as a Zouave or whether an accident or other medical condition had caused the problem later.

Another photo of AJW was posted on the Ancestry website showing him in the garden of the family home with his chicken coop. He is leaning on a stick which suggests that he was able to move about at home but going further afield might have been more of a problem. At a guess, this was probably taken after AJW and family had moved to 60 Camp Road where they were living at the time of the 1901 census. There was a long garden at the back (ideal for chickens) which looked towards terrace houses in Cross Elmwood Place – probably the windows shown in the photo. Their previous house in Alfred Place (a terrace which formed part of Carlton Street) also had a large garden at the rear but the background would have been factory buildings.

The documents passed down to AJW’s great grandson John include two very atmospheric photos of AJW, Caroline and their four children which appear to have been taken in a domestic setting (their front room?) rather than a studio.

Comparing the children with a photo from 1901, the pictures were probably taken around 1900, perhaps to mark the new century, when Agnes would have been twelve and Arthur fourteen. They have such an air of sadness about them that it suggests that they were all aware that AJW would not survive to old age. I have yet to find out what happened to Lizzie, the adopted daughter living with them in 1891.

Back row, left to right – Arthur Taylor, John Blakeley and Alexander John Wilson

Comparing the children with a photo from 1901, the pictures were probably taken around 1900, perhaps to mark the new century, when Agnes would have been twelve and Arthur fourteen. They have such an air of sadness about them that it suggests that they were all aware that AJW would not survive to old age. I have yet to find out what happened to Lizzie, the adopted daughter living with them in 1891.

Back row, left to right – Arthur Taylor, John Blakeley and Alexander John Wilson

Front row, left to right – Agnes Mary Alice, Alexander John and Caroline Wilson

Another photo posted by a descendant on the Ancestry site shows AJW Jnr wearing his Zouave uniform with talpak and what appears to be a Papal medal on his chest. The online photo is not dated but the impression is that it was taken when he was ill, later in life?

The 1901 census shows the Wilsons at 60 Camp Road with Caroline’s 86-year old mother Alice and a visitor, 20 year old Martha Bayldon who would shortly marry the eldest son Alexander (21), a mechanical and electrical apprentice engineer. Caroline was described as ‘Professor of Music and Singing’ (working from home), third son Arthur (15) was training as a metal engraver and Agnes was at school. Second son John (19) was not at home but can be found staying at Hobbin Hill, a farm in the Littlebeck Valley on the North Yorkshire Moors. Reginald Martin (19) was staying there as well, presumably a friend.

As mentioned earlier, AJW Jnr was described in the census as ‘invalid through ague’ which suggests that the family may have attributed his condition to the ongoing effects of malaria. He died, aged 56, on 24 June 1901 at 60 Camp Road. The cause of death was given as ‘Paralysis 11 years, Cerebral Congestion 1 day, Convulsions’. His wife Caroline outlived her husband by 33 years, dying in Leeds in 1934.

Sources

Powell Joseph ZP, Two Years in the Pontifical Zouaves, A Narrative of Travel Residence and Experience in the Roman States, (London: R Washbourne, 1871)

La Neuvième Croisade 1860 – 1870, Tradition Magazine Hors Serie No 13 (Paris: LCV Services, 2000)

Chadwick Owen, A History of the Popes 1830 – 1914 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998)

Baedeker K, Italy Handbook for Travellers, Second Part Central Italy and Rome (Leipsic: Karl Baedeker 1869 and 1886)

Old Ordnance Survey Maps, Central Leeds 1906, (Consett: Alan Godfrey Maps, 1988)

[i] Usually referred to as the ‘Risorgimento’.

[ii] A note on the reverse of a copy of the photo of Zouaves with Lord Denbigh and Mgr Stonor says that Alexander John Wilson was an English volunteer under Lord Vavasour of Hazelwood Castle, Bramham. It is in the handwriting of one of AJW’s grandson’s, John Graham Wilson, who was probably given the information by his grandmother Caroline (AJW’s wife).

[iii] La Neuvieme Croisade (p47) says that, according to the New York Herald of 10 June 1868, the Papal Zouaves comprised 1,190 Dutch, 1,301 French, 686 Belgians, 189 Italians, 135 Canadians, 101 Irish, 99 Germans, 50 English, 32 Spanish, 19 Swiss, 14 American, 12 Polish, 3 Maltese, 2 Russians, 1 Peruvian, 1 Circassian, 1 Indian and I Mexican.

[iv] The Dewsbury Reporter of Saturday 23 March 1872 describes the tragic end of Father Thomas Bruno Rigby – he was killed five days earlier in an accident at Green Ayre Station in Lancaster. Father Rigby was in the town for the funeral of a fellow clergyman and he and a colleague had decided to take the opportunity to drop in on a friend in Morecambe a short train ride away. While waiting for the 7pm service, he visited the ‘Gentlemen’s Apartments’ on the platform but emerged to find the train had arrived and was already on its way. Running, in an effort to reach the compartment occupied by his travelling companion, he slipped and fell between two carriages. The train stopped, but too late. His coffin was returned to Batley where hundreds gathered on the streets to pay their respects.

[v] Mgr Edmund Stonor, Chaplain to the English Zouaves in Rome wrote to newspapers in September 1868 replying to the many people who had enquired about joining the Papal Zouaves and providing answers to nine questions. The following is taken from a copy of the letter in the Tipperary Vindicator and Limerick Reporter dated 29 Sep 1868:

1. All who enter the Papal service must do so as privates, no foreign grade being accepted.

2. The terms of enlistment is for two years, or six months. If the latter, the sum of sixty francs must be paid down.

3. It is advisable to take as small an amount of clothes as possible to Rome – a few flannel shirts and socks being much needed.

4. Those who have means of their own, will find that one or two francs a day are quite sufficient to supply any extra food or wine they may require.

5. The rations of the men are the same as those of the French army, and their pay, deducting all expenses, three sous a day.

6. The committee of the Papal Defence Fund have added three sous a day of extra pay to all the English and Irish Zouaves who may require it, besides a weekly allowance of tobacco.

7. The expense of the journey to Rome is six pounds.

8. Before entering the service all must have a letter of recommendation from one of the committees and also a testimonial of good character from their parish priest.

[vi] Father Vincent Grotti

[vii] Morning Post, Monday 19 April 1869

[viii] Baedeker’s Guide to Central Italy 1869 does not mention a Restaurant de Paris but it may have been the Restaurant at the Hotel de Paris in the Via San Nicola di Tolentino.

[ix] Baedeker’s Central Italy 1869.

[x] Benjamin Thomas Holtham was born in Worcester in 1849, the son of tailor Samuel Holtham and his wife Annie. He attended Stonyhurst School (Stonyhurst School Magazine 1917, online copy).

[xii] AJW Snr’s death certificate 1886. This is the only reference to his parents I have been able to find so far in online records (UK and Canada). According to a story passed down in the Wilson family, an ancestor owned land in Canada called Wilson’s Point. There is an area with this name in the Miramichi area of New Brunswick (https://www.highlandsociety.com/wilsons-point/). An informative video on the site mentions that Scot ‘John Wilson’ settled in the area in 1784 although I have been unable so far to find a link to AJW Snr and his father James. Another John Wilson ran a ferry in the mid-19th century (he emigrated too late to be related directly related to AJW Snr and it was that John Wilson who gave his name to the area.

[xiii] Caroline sang the duet ‘Home to Our Mountains’ (Verdi) with Mr Longbottom, and solos ‘Echo Glee’ (Niethardt) and ‘She Wore a Wreath of Roses’. Cheap excursion trains ran from all over Yorkshire and Durham. She appears to have played the harmonium as well as sing. The Yorkshire Post of 2 December 1876 includes an advert placed by Miss Blakeley of 50 Belgrave Street offering a harmonium with ‘splendid tone, nine stops, walnut case’ suitable ‘for large parlour or chapel’. It seems there were no takers, as it was still for sale in the Leeds Mercury on 17 April 1877.

[xiv] The term wherry, usually used for a boat, in this instance appears to refer to some sort of waggon.

Gold afternoon Sir,

ReplyDeleteCongratulations for your highly documented article ! As I am myself working on English Papal Zouaves, I would be effectively interested in using some of your photos, especially that from the Universe 1929. You will of course be quoted. Could it be possible ?

Duncan PROUX

Many thanks for your kind comments - they are much appreciated. I would be very happy for you to use any of the photos or information in this article, with a reference to their source, and look forward to seeing to the results of your work. Kind regards K (madam rather than sir!)

ReplyDeleteThank you - absolutely fascinating and what wonderful photos. I too am researching the English Zouaves and hope to write something on the subject. It would be wonderful if I could use some of your photos etc if appropriate, with acknowledgements. That would be much appreciated! According to the published list of Zouaves, AJW's matriculation number was 8123, he enlisted on 31 October 1868 but (according to the list I gave) was discharged on 21 September 1870, the day the Zouaves were effectively disbanded following the Fall of Rome the previous day. Best wishes, Fr Nicholas

ReplyDelete